By Ilya Umanskiy, CFE | Partner, Sphere State

Introduction: The Bridge Between Code and Court

In my years transitioning from traditional investigations at Kroll to the specialized world of cryptocurrency recovery at Sphere State, I have learned that while the blockchain is immutable, the truth in a courtroom is often malleable. As blockchain investigators, we deal in hashes and hex data; as expert witnesses, we deal in persuasion and clarity.

Expert testimony is needed increasingly often as the total case count involving Web2 and crypto rises. The content of the expert report can vary from straightforward questions regarding the characteristics of a certain token, to complex trace matters involving the origin of funds.

This guide is distilled from my work in cross-border asset recovery and identifying real-world assets behind anonymous wallets. It is written for the practitioner who wishes to elevate our industry—to ensure that our work stands up not just to the scrutiny of a block explorer, but to the rigor of cross-examination.

Phase I: The Pre-Engagement Assessment

“Resilience is not just for systems; it is for your case theory.”

Before you accept an instruction, you must apply the same “viability check” you would to a recovery case.

1. Defining the Scope of Expertise

Courts are increasingly inundated with cases along a very wide spectrum of technologies associated with Web3 and blockchain infrastructure. Therefore, it is challenging for a single practitioner to possess wide-spectrum expertise. Whether you are testifying on the mechanism of a DeFi rug pull, the valuation of an illiquid token, or tracing ETH/ERC-20 flows through mixers like Tornado Cash—if the case requires specific knowledge of a niche protocol or technology you haven’t worked with extensively, do not take it. Your credibility is your only currency; do not spend it on speculation.

2. The Conflict & Independence Check

In the Web3 ecosystem, degrees of separation are fewer than you think. Verify that you have no prior on-chain or off-chain relationship with the involved addresses or entities (e.g., having used the same exchange deposit address). Independence is absolute.

Phase II: The Investigation & Methodology

“On-chain evidence is the skeleton; off-chain intelligence is the flesh.”

A wallet address is not a defendant. To serve the court, you must bridge the gap between digital anonymity and legal identity.

1. The Hybrid Approach

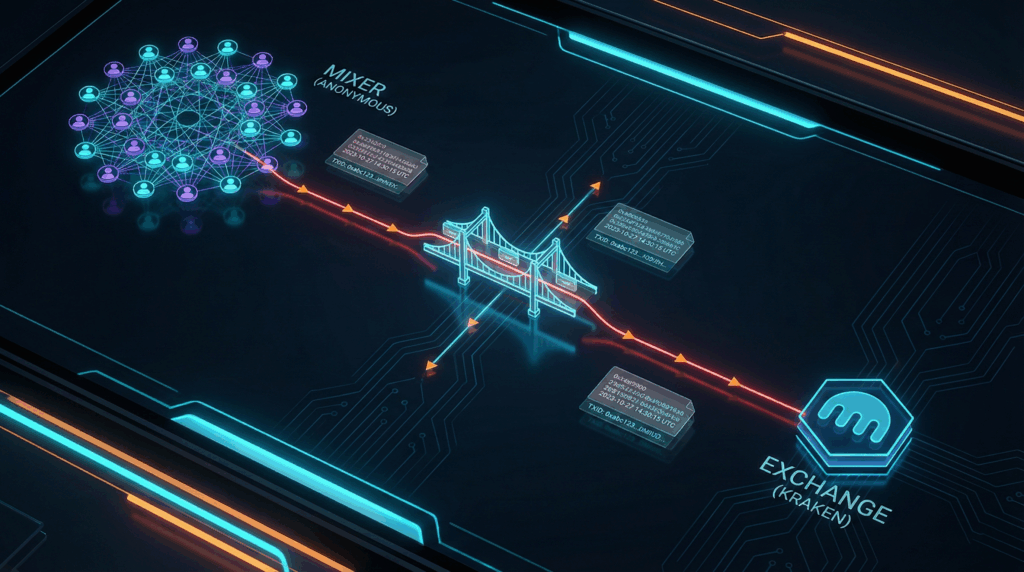

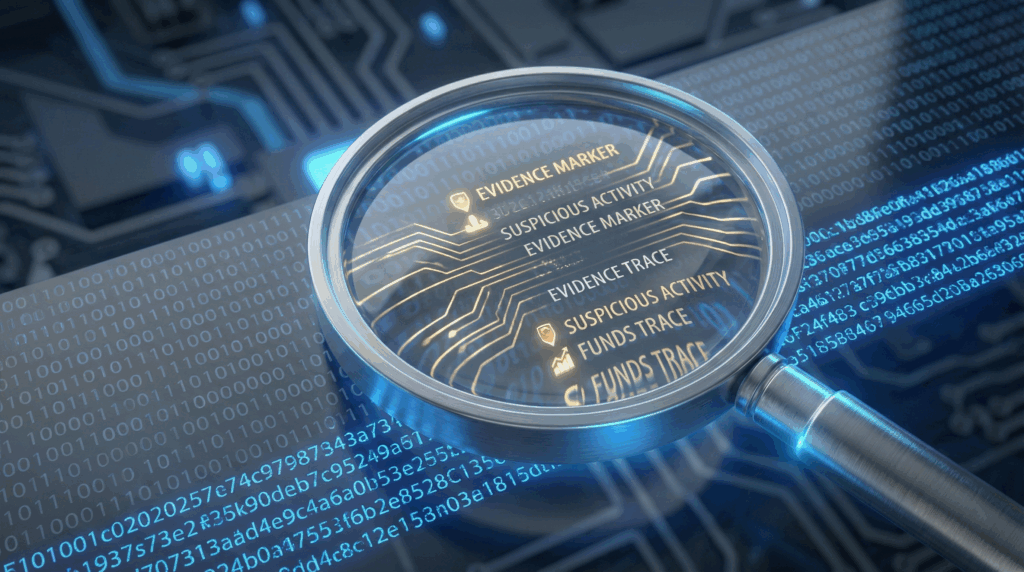

Do not rely solely on automated clustering heuristics from tools like Elliptic or Chainalysis. You must validate these findings manually and at the transaction level. My methodology at Sphere State involves bundling on-chain forensics (tracing token swaps, bridge movements) with off-chain signals (IP indicators, KYC hits, social engineering leaks).

2. Why Granularity Matters

In my article “A Failure to Plan,” I wrote about the danger of lacking “granularity” when managing crises. The same applies here. A report stating “Funds went to Binance” is insufficient. A court-ready report states: “70% of funds were swapped for USDT on Curve, bridged to Tron, and deposited into a specific Binance user cluster associated with known high-risk OTC desks.” Then, substantiating exhibits are referenced to complete the chain of your analysis.

Phase III: Drafting the Expert Report

“Complexity is the enemy of justice.”

Judges and arbitrators are not typically blockchain natives. Your report must translate specialist findings into judicial clarity. You need to make the non-specialist feel comfortable with the logic of your findings.

1. The “Plain English” Standard

Avoid jargon where possible. If you must use it, define it. Do not say, “The attacker executed an address spoofing attack.” Say, “The attacker exploited the victim’s inattention to divert funds—similar to a pickpocket who distracts a passerby.”

2. Visualizing the Flow

A clear visualization is worth ten pages of text. Use diagrams, flowcharts, and relationship matrices to demonstrate the key points of your analysis.

3. Focus on Admissibility

Every claim must be substantiated by reproducible evidence. List the transaction hashes (TxIDs) for every hop. Ensure your report adheres to the specific procedural rules of the jurisdiction (e.g., CPR Part 35 in the UK/Wales, Federal Rules of Evidence 702 in the US).

Phase IV: Testimony and Cross-Examination

“The Human Element is always the wildcard.”

I have long argued that the human element is the weakest link in fraud risk management; in court, it is the deciding factor.

1. Demeanor and Resilience

Opposing counsel will try to introduce a “wildcard element”—an unexpected question to rattle you. They may question the reliability of your tracing software or get you to speculate about the probability of false positives in clustering. Remain calm. Acknowledge limitations honestly.

2. The “Teacher” Mindset

Do not lecture the judge; teach them. Your goal is to make the trier of facts feel smart. When they understand the mechanism of the fraud because of your explanation, they are more likely to accept your conclusion. Once again, just like in your narratives, avoid jargon and technical terms—use plain language as much as possible.

Conclusion: A Call to Standardize

I am proud to have contributed to the “Crypto Market Consumer Bill of Rights” as a member of the Crypto Market Integrity Coalition (CMIC) to help build transparency and an easier path to justice for crypto fraud victims. It is our duty to ensure that our contributions to the legal system are as immutable and transparent as the ledgers we analyze. By adhering to strict procedural rigor and maintaining unwavering ethical standards, we help the next generation of practitioners build a safer ecosystem for all.

About the Author: Ilya Umanskiy is a Certified Fraud Examiner and a Specialist Crypto Investigator (Elliptic). He has delivered multiple industry talks, written numerous thought pieces on fraud risk management and resilience, and taught in the Master’s Degree Program at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.