Securing a Building Isn’t About the Grant. It’s About the Door.

Getting a grant approved feels like a win. For many organizations, it’s the moment everyone exhales. But that letter isn’t the finish line—it’s the point where things actually start to matter.

Because once the funding is in place, you still have to turn dollars into real security. And that’s where mistakes happen.

Doors get reused because “they look fine.”

Locks get chosen because they’re familiar.

Vendors promise solutions that sound secure but fall apart under scrutiny.

In security, assumptions are dangerous. A door is not just a door. A lock is definitely not just a lock. And when the hardware doesn’t match the threat, all you’ve really purchased is a false sense of protection.

This article is about the physical reality of securing a perimeter. Not cameras. Not policies. Not paperwork. Just doors, frames, locks, and the decisions that separate real resistance from the illusion of it.

Start With the Door, Not the Technology

Most security failures don’t start with electronics. They start with the door itself.

Walk into almost any community center or house of worship built in the last few decades and you’ll see the same thing: aluminum storefront doors with lots of glass. They look open and inviting. They also happen to be one of the weakest perimeter options available – the only worse alternative being no door whatsoever.

Storefront doors usually have very narrow metal housings with lots of glass. There simply isn’t enough metal there to properly anchor serious hardware. Under force, these doors flex, frames bend, locks pull away, glass shatters.

A determined attacker doesn’t need to defeat the lock. They just need to deform the door enough for the latch to slip. They can also simply break a large glass pane.

If your budget allows for replacement, this is where money should go first. Storefront doors with thicker metal housings are better, but hollow metal doors are the gold standard. They’re rigid, stable, and designed to take abuse without warping.

Solid core wood doors can work too, but only if you understand their limitations. Wood moves. Temperature and humidity matter. Once you get into tall exterior wood doors—especially over eight feet—you’re asking for alignment problems. And alignment problems turn locked doors into unsecured ones.

Why the Lock You Choose Matters More Than You Think

One of the most common—and costly—mistakes in security upgrades is using residential-grade locks on commercial perimeter doors.

If the key goes into the knob or lever, you’re looking at a cylindrical lock.

Securing a Building Isn’t About the Grant. It’s About the Door.

Getting a grant approved feels like a win. For many organizations, it’s the moment everyone exhales. But that letter isn’t the finish line—it’s the point where things actually start to matter.

Because once the funding is in place, you still have to turn dollars into real security. And that’s where mistakes happen.

Doors get reused because “they look fine.”

Locks get chosen because they’re familiar.

Vendors promise solutions that sound secure but fall apart under scrutiny.

In security, assumptions are dangerous. A door is not just a door. A lock is definitely not just a lock. And when the hardware doesn’t match the threat, all you’ve really purchased is a false sense of protection.

This article is about the physical reality of securing a perimeter. Not cameras. Not policies. Not paperwork. Just doors, frames, locks, and the decisions that separate real resistance from the illusion of it.

Start With the Door, Not the Technology

Most security failures don’t start with electronics. They start with the door itself.

Walk into almost any community center or house of worship built in the last few decades and you’ll see the same thing: aluminum storefront doors with lots of glass. They look open and inviting. They also happen to be one of the weakest perimeter options available – the only worse alternative being no door whatsoever.

Storefront doors usually have very narrow metal housings with lots of glass. There simply isn’t enough metal there to properly anchor serious hardware. Under force, these doors flex, frames bend, locks pull away, glass shatters.

A determined attacker doesn’t need to defeat the lock. They just need to deform the door enough for the latch to slip. They can also simply break a large glass pane.

If your budget allows for replacement, this is where money should go first. Storefront doors with thicker metal housings are better, but hollow metal doors are the gold standard. They’re rigid, stable, and designed to take abuse without warping.

Solid core wood doors can work too, but only if you understand their limitations. Wood moves. Temperature and humidity matter. Once you get into tall exterior wood doors—especially over eight feet—you’re asking for alignment problems. And alignment problems turn locked doors into unsecured ones.

Why the Lock You Choose Matters More Than You Think

One of the most common—and costly—mistakes in security upgrades is using residential-grade locks on commercial perimeter doors.

If the key goes into the knob or lever, you’re looking at a cylindrical lock.

These are fine for houses and interior rooms. They are a poor choice for exterior doors that matter.

Cylindrical locks rely on short latch bolts and the physical strength of the knob itself. A hard strike can shear the knob off entirely. Even without brute force, the short latch throw makes them easy to pry if the door shifts even slightly out of alignment—which happens in almost every building over time.

Mortise locks are built for a different world.

These are fine for houses and interior rooms. They are a poor choice for exterior doors that matter.

Cylindrical locks rely on short latch bolts and the physical strength of the knob itself. A hard strike can shear the knob off entirely. Even without brute force, the short latch throw makes them easy to pry if the door shifts even slightly out of alignment—which happens in almost every building over time.

Mortise locks are built for a different world.

With a mortise lock, the cylinder is separate from the handle, and the entire mechanism sits inside a steel pocket in the door. These locks are designed to be abused. The latch throw is deeper. The dead latching is real. Once the door closes, the latch is mechanically frozen in place.

You can’t slide it back with a tool. You have to operate the lock.

That distinction alone stops an enormous number of forced-entry attempts.

When Electronics Make Things Worse

Electronic access control is where good intentions often create new vulnerabilities.

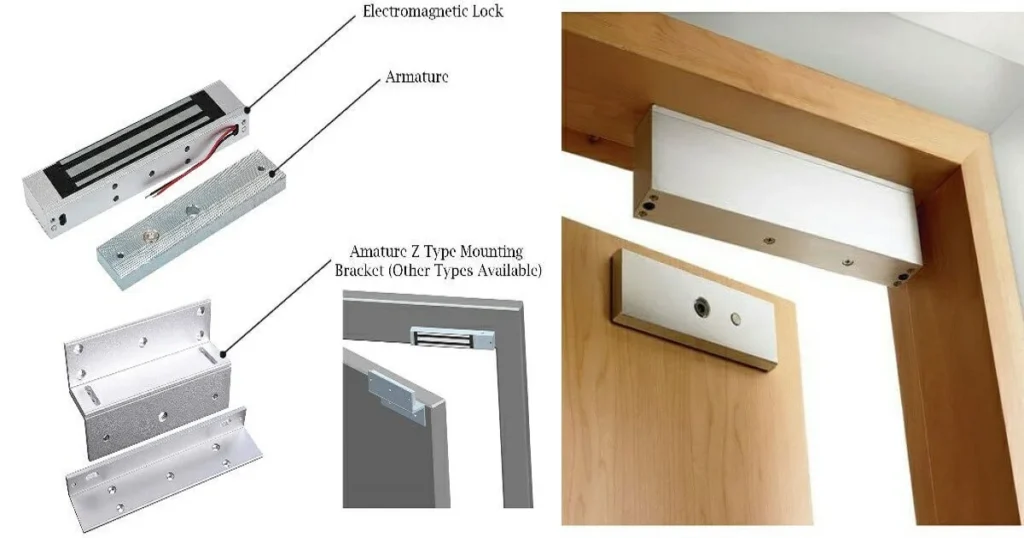

Magnetic locks are a perfect example. They’re common, familiar, and often pitched as a clean solution for access control. On paper, a maglock sounds impressive—over a thousand pounds of holding force.

With a mortise lock, the cylinder is separate from the handle, and the entire mechanism sits inside a steel pocket in the door. These locks are designed to be abused. The latch throw is deeper. The dead latching is real. Once the door closes, the latch is mechanically frozen in place.

You can’t slide it back with a tool. You have to operate the lock.

That distinction alone stops an enormous number of forced-entry attempts.

When Electronics Make Things Worse

Electronic access control is where good intentions often create new vulnerabilities.

Magnetic locks are a perfect example. They’re common, familiar, and often pitched as a clean solution for access control. On paper, a maglock sounds impressive—over a thousand pounds of holding force.

But here’s the reality: maglocks are fail-safe by design. Lose power or trigger the fire alarm, and the door unlocks. Cut electricity, and your perimeter opens.

That means your security depends entirely on continuous power.

Then there’s the exit motion sensor.

But here’s the reality: maglocks are fail-safe by design. Lose power or trigger the fire alarm, and the door unlocks. Cut electricity, and your perimeter opens.

That means your security depends entirely on continuous power.

Then there’s the exit motion sensor.

Most maglocks rely on a PIR sensor to unlock the door as someone approaches from the inside. These sensors are notoriously easy to trick. Warm air. Paper slipped through a gap. A simple tool in the right place.

The result is a door that can be unlocked from the outside without ever touching the reader.

There are situations where maglocks are unavoidable—certain glass assemblies leave no alternative—but they should never be the default.

A better approach is to keep the door mechanically secure and add electronics to the lock itself.

Electric strikes are common, but they introduce a moving part into the frame. Under impact, that keeper becomes the weak point.

Most maglocks rely on a PIR sensor to unlock the door as someone approaches from the inside. These sensors are notoriously easy to trick. Warm air. Paper slipped through a gap. A simple tool in the right place.

The result is a door that can be unlocked from the outside without ever touching the reader.

There are situations where maglocks are unavoidable—certain glass assemblies leave no alternative—but they should never be the default.

A better approach is to keep the door mechanically secure and add electronics to the lock itself.

Electric strikes are common, but they introduce a moving part into the frame. Under impact, that keeper becomes the weak point.

Electrified mortise-type locksets avoid that problem entirely. The door stays latched. The electronics only control whether the outside handle works. When someone kicks the door, they hit steel—not a small mechanical release.

What to Do When Replacement Isn’t an Option

Not every building can be gutted and rebuilt. Historic properties, limited grants, and phased projects are realities.

The good news is that targeted retrofits can still add meaningful resistance.

Latch guards are a great example. They’re simple metal plates that cover the gap between the door and frame near the lock. They aren’t pretty. They are extremely effective. A crowbar can’t reach what it can’t access.

Electrified mortise-type locksets avoid that problem entirely. The door stays latched. The electronics only control whether the outside handle works. When someone kicks the door, they hit steel—not a small mechanical release.

What to Do When Replacement Isn’t an Option

Not every building can be gutted and rebuilt. Historic properties, limited grants, and phased projects are realities.

The good news is that targeted retrofits can still add meaningful resistance.

Latch guards are a great example. They’re simple metal plates that cover the gap between the door and frame near the lock. They aren’t pretty. They are extremely effective. A crowbar can’t reach what it can’t access.

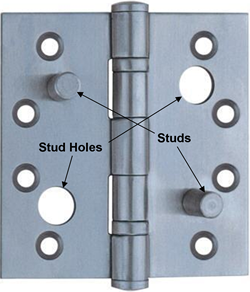

Exposed lock cylinders are another weak point. If a cylinder can be gripped, it can be twisted out. A spinning collar removes that leverage entirely.

Outward-swinging doors bring hinge problems. If the pins are exposed, the door can be removed even if it’s locked. Security hinges or non-removable pins solve that issue without changing the door itself.

These aren’t high-tech solutions. They’re practical ones.

Glass Is Always the Compromise

Vision panels in door loafs are often necessary. Blind doors create safety issues. But glass placement matters more than most people realize.

If someone can break glass and reach the handle, the door is compromised. Glass should be narrow and placed as far from the locking hardware as possible.

These aren’t high-tech solutions. They’re practical ones.

Glass Is Always the Compromise

Vision panels in door loafs are often necessary. Blind doors create safety issues. But glass placement matters more than most people realize.

If someone can break glass and reach the handle, the door is compromised. Glass should be narrow and placed as far from the locking hardware as possible.

And despite what many people believe, wire glass is not a security feature. The embedded wire actually makes the glass weaker by creating fracture points. It was designed for fire containment, not impact resistance.

If replacement isn’t possible, anchored security films can significantly improve resistance. Laminated glass or polycarbonate is even better.

Security Still Has to Follow the Code

No matter how serious the threat is, life safety always comes first.

Egress doors must allow people to exit with a single motion. No keys. No combination. No second step. Double-cylinder deadbolts on exit doors are not just dangerous—they’re illegal.

Fire Marshals have the authority to shut facilities down over non-compliant hardware. Improper modifications can avoid fire ratings and insurance coverage. These aren’t theoretical risks.

Good security works with the code, not against it.

The Real Takeaway

Security isn’t about buying the most advanced system. It’s about choosing the right components for the threat.

A mechanically sound door with a proper mortise lock will outperform an expensive electronic system built on weak hardware. Every time.

Start with the shell. Strengthen the door and frame. Choose hardware that resists force. Add technology only after the fundamentals are solid.

That’s how you move from looking secure to being secure.

And despite what many people believe, wire glass is not a security feature. The embedded wire actually makes the glass weaker by creating fracture points. It was designed for fire containment, not impact resistance.

If replacement isn’t possible, anchored security films can significantly improve resistance. Laminated glass or polycarbonate is even better.

Security Still Has to Follow the Code

No matter how serious the threat is, life safety always comes first.

Egress doors must allow people to exit with a single motion. No keys. No combination. No second step. Double-cylinder deadbolts on exit doors are not just dangerous—they’re illegal.

Fire Marshals have the authority to shut facilities down over non-compliant hardware. Improper modifications can avoid fire ratings and insurance coverage. These aren’t theoretical risks.

Good security works with the code, not against it.

The Real Takeaway

Security isn’t about buying the most advanced system. It’s about choosing the right components for the threat.

A mechanically sound door with a proper mortise lock will outperform an expensive electronic system built on weak hardware. Every time.

Start with the shell. Strengthen the door and frame. Choose hardware that resists force. Add technology only after the fundamentals are solid.

That’s how you move from looking secure to being secure.